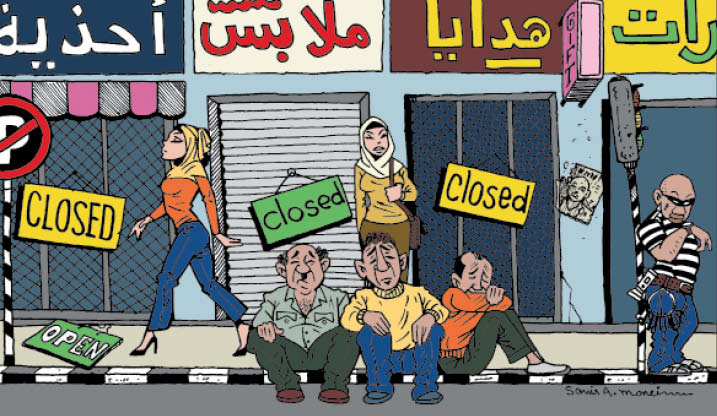

In an NDJ World ranking of the 10 cities that never sleep, Cairo, unsurprisingly ranked first. But this may change soon.

In a bid to confront serious power shortages before this turns into a chronic crisis, the government is considering passing a law that will force stores to close at 10 pm after Eid al-Adha.

Coffee shops and restaurants, however, will be allowed to extend working hours to midnight, while both touristic establishments and pharmacies will be exempted from the law.

Egypt has been suffering one of its biggest power failures since the beginning of summer. Several Cairo districts regularly experience a temporary electricity outage due to the enormous strain imposed on the national grid during the hot season, as well as a fuel crisis that’s hit most parts of the country.

Though the drafted law, which has been approved by the Board of Governors and Prime Minister Hesham Qandil, has not seen the light yet, it has already been provoking widespread controversy.

Ahmed El-Wakil, the head of the Federation of Egyptian Chambers of Commerce, condemned the bill on the grounds that the Chamber of Commerce was not consulted about the decision, as it should have been according to the law, before being implemented.

The proposal draft has also been met with heavy public criticism on a range of issues, which the government turned a blind eye to.

“The bill obviously lacks a studied decision-making process,” says Hussein Ismail, an employee at the Defense Ministry and owner of a supermarket. He believes the government has not improved its willingness to listen, as was the case during the old regime.

Ismail points out that the government was supposed to conduct a survey across governorates to gain new insight into the current situation of the country and consequently devise a solution that works best for the Egyptian people.

Assem Marzouq, an engineer who works the night shift in a supermarket as a cashier to increase his income, believes that the bill would hit the incomes of many poor people, keeping them out of jobs.

“If this law is implemented, night shifts would be cancelled. Who would want to hire extra people and pay salaries while stores are already shutting down early and suffering a decline in revenue?” Marzouq says.

He claims that officials are wringing their hands about the power shortages while lacking the willingness to work towards actual solutions to ensure a supply of electricity.

In August, Qandil called on people to ration their electricity consumption by cutting down on excessive air conditioning use and wearing cotton clothing for the hot weather. The prime minister’s statements stirred the anger of many for placing the blame directly on people’s shoulders, rather than adopting remedial measures to increase the capacity of the national grid.

However, the tolls will be variable. The drafted law seemingly will not have the same level of disadvantage on higher-income people.

Essam Alaa, an owner of an upscale restaurant and coffee shop in Mohandessin, says he would support the bill if it was fairly imposed on all without exemptions.

“My business wouldn’t be greatly affected by closing two hours earlier than usual. Midnight usually does not drive customer traffic anyway,” he says, hoping the bill would be an effective substitute for experiencing long-hours of blackout.

In low-income neighborhoods, the situation of economically disadvantaged people has another face. Essam Shabaan, a waiter in a small downtown ahwa, expresses a decidedly different view.

“Customers stay until the late-night hours, especially young people who have nothing to do at night. So, if I reduce my work hours, this means I’ll lose big tips, which is the main source of my livelihood,” says Shabaan, who works daily from 12 pm till 4 am for LE200 per month.

The potential drawbacks of turning off the lights earlier than usual are not limited to causing economic deterioration for particular segments of society. Insecurity also poses a real threat with a troubling increase in shoplifters and other criminals; especially with the poor police presence in the streets after a security vacuum opened up in the aftermath of the 25 January revolution.

“The country is already suffering from high crime rates and is in dire need of public safety, not opening the way for more criminals who might use the cover of darkness to conceal their illegal activities,” says Afaf Mourtada, a teacher.

Changing decades-long habits of late-night shopping has serious ramifications that could pose an obstacle to enforcing the proposed law, Mourtada points out.

“Most people are done with work around 5 pm. So, this would definitely cause traffic paralysis after then because the streets would be packed with people to buy what they need before 10 pm.”

Though the proposed law stipulates that stiff penalties for violations will be imposed ranging from fines to imprisonment, Shabaan refuses to shut down his business early saying, “If this law is implemented, I’d protest in front of the presidential palace because I have no other substitute for earning my bread,” he says.

Similarly, Ismail is ready to pay a fine, but not to close early. He suggests the government provide other effective mechanisms for confronting regular power cuts. “Why doesn’t the government take extra taxes to establish more electricity stations, instead of burdening us with penalties and ruining our business?” Ismail says.

“It (the bill) goes against the nature of Egyptians. The government wrongly puts itself first with no consideration of what benefits us better,” Mourtada concludes.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.