LONDON – The Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A) announced Monday that artist Rachid Koraichi is the 2011 winner of the Jameel Prize, a prestigious award that comes with 25,000 British pounds. Koraichi was chosen from a shortlist of 10 other candidates and 200 nominees from across the globe.

Koraichi paid tribute to fellow nominees and the Egyptian craftsmen who helped make his winning piece saying, “The prize is shared with the artisans in Cairo."

His piece, entitled “Les Maitres Invisibles” (The Invisible Masters, 2008), was three years in the making and comprises 99 vast, white hanging canvases adorned with Arabic calligraphy and an array of symbols and patterns that invoke the traditions of 14 Islamic mystics, from Ibn al-Arabi to Rumi. Only six of the total 99 banners hang from the ceiling of the Jameel Gallery in this exhibition. The number 99 is, of course, significant in Islam, but Koraichi adds a layer of meaning by giving each of the 14 represented mystics seven banners, with the final one reserved for God.

The Jameel Prize is a biannual award started in 2009 – first given to Afruz Amighi for her work “1001 Pages” (2008) – for contemporary art inspired by Islamic traditions, design and craftsmanship. The shortlisted artists’ work has been on display at the V&A since July 2011 and will soon be shown on an extensive international tour.

The award was presented by Hasan Jameel, of Abdul Latif Jameel Community Initiatives, which sponsors the prize, Martin Roth, V&A director and Culture, Communications and Creative Industries Minister Ed Vaizey, who described the award as an “icon in our cultural landscape."

Koraichi's work is steeped in Islamic tradition and history, yet he sees these banners as speaking a universal language through repeated ciphers, which he describes as “symbols of humanity.”

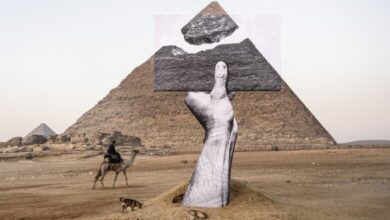

“There is the symbolism of the hand; the open hand symbolizes peace,” and is a motif used throughout human history since cave paintings, he says.

In the workshops where these pieces were created, he employed an applique technique still used in Cairo today but one, he explains, that dates back to pharaonic times, when it was used on linen strips during mummification. This continuity of tradition is deeply embedded in the piece to create a delicate balance between the ancient and modern worlds that are also part of his personal story. Koraichi, who was born into a Sufi Algerian family in 1947, lives between Tunisia and France and traces his family lineage back to Mecca; he makes the rich history of his own mystical and Islamic heritage accessible and new.

Koraichi’s work “was very unique, it follows very old traditional beliefs and it takes them into the contemporary world in a creative way and you can imagine that these pieces still in the future will present themselves as beautiful works of art,” says Dina Bakhoum, conversation program manager of the Aga Khan Trust in Egypt, who was on the panel of four judges that selected the winner.

The shortlist for this prize was diverse, spanning a variety of media and artists in various stages of their careers. Established artists such as Koraichi and Monir Farmanfarmaian, who has been creating mirror mosaics for five decades, competed with nominees such as recent college graduate Noor Ali Chagani, who creates sculptural pieces from tiny bricks in his version of Mughal miniature painting, which he studied at the National College of Arts in Lahore.

Yet a common thread of crossing time and place seems to run through the collection, in what Bakhoum calls a “timelessness” that was “one of the things that we really felt inspiring in many of the pieces,” she adds. All those who were shortlisted have varying degrees of mixed-cultural identity and rely on the incorporation of traditional techniques and themes to create very modern and distinctive art.

Iranian-North American Babak Golkar’s work is a prime example of this overlap and cultural hybrid. His piece, “Negotiating Space for Possible Coexistences, No. 5” (2011), pulls crisp white architectural models out of the patterns and shapes of traditional Persian carpets, resulting in a creative tension between minimalist modernity and ornate decoration.

“Viewpoint becomes really important,” says Golkar, as the structures stand tall as a cityscape when viewed from the side but collapse back into the carpet when viewed from above, giving way to a constant shifting and uncertainty.

Soody Sharifi plays on her mixed Iranian-American identity as well. She imposes photographs taken in modern Tehran onto traditional Persian miniature paintings to create “Maxiatures” with titles like “Fashion Week” (2010) that inform the viewer that they are not the traditional scenes they appear to depict at first glance. Transforming a much-venerated and long-established art form, Sharifi says “with each one I create new stories that depict everyday life.”

Hazem al-Mestikawy’s “Bridge” (2009) typifies this idea of crossing cultures, and indeed the title captures much of what this exhibition is about. Based around a single geometric shape, he constructs two mirror-image city-like structures from recycled paper and cardboard, with one covered in Arabic newspaper clips, the other in English, connected by a central “bridge” that is solid and covered in both languages. The shape itself resembles the letter “I” and adds further depth of meaning to the piece.

“It’s the ‘I’ as a letter and it’s also a very old pattern that exists in the Indo-Persian tradition,” explains Mestikawy, “this shape opened a lot of ideas for me; I built a city out of it.”

Egyptian-born Mestikawy lives between Cairo and Vienna, but this piece is not purely autobiographical. It’s not just about his own identity hanging between East and West, but reaches for something more universal as well.

“It’s not just ‘I’,” he says, “also it’s you. … It’s all of us.”

This is quite typical of Mestikawy, whose geometric and minimalist structures are often conceptually more than they seem. He deconstructs language and letters, plays with negative spaces to create further dimensions and hidden spaces and continually uses the number nine and the square, which he sees as “the basic element of geometric repetition."

Mestikawy’s concept of a bridge also fits very well with the overarching themes and the wider context of the Jameel Prize, as, in the words of Martin Roth, the prize is “promoting cultural links and understanding” and also “contributes to broader debates about Islamic culture.”