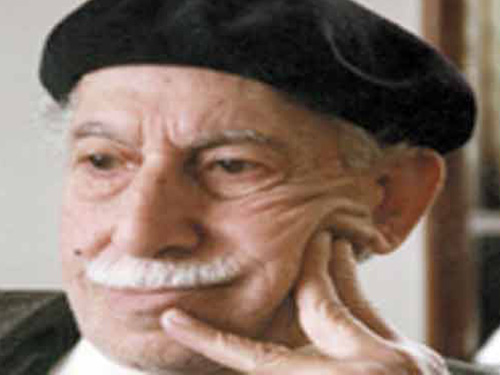

On 3 March 1978, Egyptian literary pioneer Tawfiq al-Hakim wrote in state-run Al-Ahram newspaper, “Arabs now have money and men. There is no doubt that they have reached adulthood and they do not need to burden Egypt with their problems.”

Hakim went on to say, “As for Egypt’s army, it should be a defensive one, strong and equipped with modern weapons not to attack and assail, but to protect its neutrality.”

The call implied that Egypt should ignore the strategic alliance former President Gamal Abdel Nasser had forged with the Arab world since the 1950s. It disregarded the slogan of Arab unity, suggested instead that Egypt could settle its differences with Israel without consulting other Arab countries.

Hakim’s call for Egyptians to dig into their past and discover their own identity stirred heated debate at the time. Pan-Arab intellectuals such as Yusuf Idris and Raja al-Naqqash said the Arab component was integral in shaping Egypt’s modern identity.

But others supported Hakim’s vision — an extension of notions of identity from Egypt’s “liberal era” (1919–1952), when the country’s intelligentsia had argued that the nation’s ancient civilization should be an inspiration and tool to shape a modern Egyptian identity.

Hafez Ibrahim, one of the founders of modern Arab poetry, used this pharaonic inspiration to write his well-known poem “Egypt Talks About Herself.” He wrote, “All peoples stood, watching how I build the bases of glory alone/And the Pyramids’ builders — long ago — spoke for me at challenge/My glory is deep in history, who has a glory like mine?”

Meanwhile, Naguib Mahfouz started his career writing novels that explored themes from ancient Egypt, such as “Whisper of Madness” (1938), “Mockery of the Fates” (1939), “Rhadopis of Nubia” (1943) and "The Struggle of Thebes" (1944). Here Mahfouz was influenced by thinker Salama Moussa's advocacy of a continuous pharaonic identity of Egyptians.

This notion of identity can also be found in Hakim’s earlier works, such as his 1933 novel “Return of the Spirit,” where he championed the idea that Egyptian history ran without interruption. He also wrote a letter to Taha Hussein, saying, “We were almost fainting without any sense of ourselves … We rather saw the old Arabs … Our admixture with the Arab soul was about to make us forget that we have a pure [Egyptian] soul.”

When the Free Officers Movement started looking for new strategic alliances in the 1950s and promoting Arab unity, however, it suppressed such calls for fear that searching for such an identity would undermine the idea of Arab unity.

Hakim’s 1978 article also followed a period when state-run newspapers wrote extensively about Egyptian causalities in the Arab-Israeli wars, compared to the “tiny Arab contribution to the military” efforts to fight Israel. The conclusion of such coverage was that Arab nationalism was a burden. Taking into account the worsening economic situation of the time — Hakim’s article followed the 1977 food riots — some writers, including Mahfouz, concluded that Egypt’s desperate economic situation was caused by its perpetual military battles with Israel, while other Arab states just sat back and watched.

Indeed, a few months later, former President Anwar Sadat adopted the core of Hakim’s call by visiting Jerusalem. Two years later, Egypt became the first Arab country to sign a peace treaty with Israel.