Ask about ideas of progress in Egypt and you’ll commonly hear: malls and villas away from downtown Cairo, American coffee at some neighborhood Cilantro or, for those living in Upper Egypt or the Delta, a better life in Cairo.

On the other hand, the sight of donkeys on the streets, men dressed in galabeyas, or even the ancient, wrecked black taxis give shivers to many at worse, or elicit nostalgic feelings of the good ol’ days long gone at best.

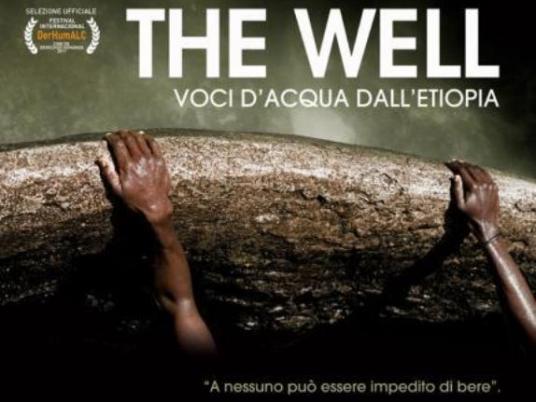

Transpose this tradition versus the progress dilemma in rural southern Ethiopia, and you get “The Well,” a documentary on the hardships of the Borana people to access water, written by Mario Michelini, and directed by Ricardo Russo and Paolo Barberi.

“[Russo and I] always wanted to make movies. We wanted to be activist journalists,” said Michelini at the movie screening Sunday at the Italian Cultural Institute in Zamalek.

But life had other plans that led him to the humanitarian world. During a two-year posting in Ethiopia working with a non-governmental organization on sustaining communities through access to water, he became interested in the Borana people and their wells.

“I wanted to know about the people and how they manage water in a region where water is scarce,” he said. He developed the script during his stay and sent it to Russo, a childhood friend who had already directed a few short films.

The result of their effort is a languishing account of duress and Sisyphean struggle that combines dramatic photography of the Ethiopian savanna with detailed narration of the Borana’s predicaments.

The Borana are semi-nomadic shepherds and herdsmen who live in southern Ethiopia, on the border of Kenya. Their livestock is far from being a source of food (they mostly eat seeds and rice); it is a hedge to limit damages in difficult times. They can raise thousands of horses, cows, camels, goats, and sheep.

Unfortunately, their land was not graced with wild rivers, and droughts that used to occur on a seven-year cycle, now come back every two or three years.

“If there’s no rain, our life is in danger,” says one elder, summarizing the situation early on in the movie.

Their only source of water during the dry season is vertiginous deep open-pit wells. To bring the water to the surface and allow the livestock to drink, a human chain of men must carry the water, passing buckets up and down to one another.

Who can drink at the well, and when, is regulated by many ancestral rules, since water is not sufficient for everyone.

But one thing is for sure: when it’s time to bring water to the troughs, everyone must participate, whether your herd is drinking that day or not. This is a community effort, and this is what drives the Borana people.

So when foreign aid was sent to the Ethiopian government and non-governmental organizations arrived to install a motorized pump in one of the towns, traditions were eluded and the Borana elders slowly saw their inherited way of life disappearing.

Michelini’s script is careful at balancing the pros and cons of the traditional wells. His objectivity is stellar: all the facts necessary to form one’s opinion are at hand, yet one is left pondering the dilemma long after the ending credits have rolled.

Or maybe it is less objective and more about his inner conflict, considering his work in the humanitarian field. Well-intentioned people strive at improving people’s lives, but sometimes, their ideas are at odds with centuries-old traditions, and may leave communities confused once change has come.

This is a story with which some Egyptians are familiar. To name but one example, Amr El Leithy, host of a new TV talk show, launched Hamlet Al-Milliar Lel Nohood Bi Al-Ashywayat (The Billion Pound Campaign to Develop Slums) early in 2011, to build new homes for slum residents, without their prior consultation.

Such efforts bring questions like, is that really what the supposed beneficiaries want, when they don’t even have access to medical clinics or schools? And who decides what comes first — the residents, or the people with the money?

Back in Ethiopia, a Borana elder is reticent as to how business runs at the modern pump. To activate it, one has to buy fuel, meaning that the richest have access to more water, bringing capitalism to water management. This spoils everything for which the Borana have stood when it comes to managing their water; the sense of community that surrounded the resource has been lost, and it is also a breach of the sacrosanct tradition of not exchanging anything at the pump.

At the traditional wells, water was always limited, but everybody had equal access to it, and it was forbidden to buy more of it through any trade or gift.

Other improvements have been more welcomed by the community, and they are the ones that integrate their wishes, such as the reconfiguration of some wells to increase efficiency.

As one waterman puts it, the Borana need “educated people” to help them improve their lifestyle, but changes have to be done slowly. “We never expect our tradition to die,” he says.