It is a motley crew that finds shelter in Tahrir Square these days. On the afternoon of 7 April, a man at a tea stand wanted to see off a youth and so threw a glass mug at him. It missed the youth and hit someone next to him, shattering into tiny fragments on his head. The man made a brief apology as he turned around to sit back down and his victim raised his hand in the air and said, "No problem," as he staggered away.

Behind them was a filthy child of around two, naked except for a dirty t-shirt, his hair a great blonde halo of mess. Cars slowed down to avoid him as he pottered about in the road watched by his mother and two other children lying in the grass behind her.

On the corner of Talaat Harb Street and Bab el-Luq are lurking men. One is confronted, and he responds, “You’re talking to a convicted criminal. I’m in control of the whole square."

Behind him, on the sad grassy island, there was a protest of six people, one of whom was banging a drum. Their sign read, “We want to live.”

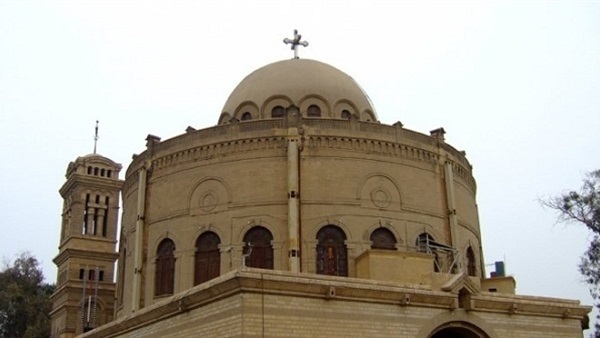

Earlier that day, a funeral march from the Abbasseya Coptic Orthodox cathedral for Christian victims of violence in a place about an hour outside central Cairo had been attacked. As usual there has been intense and pointed enquiries about how events at the cathedral started (the story goes that some of the mourners themselves attacked parked cars, provoking a response from Abbasseya locals who rarely tarry in neighbourhood watch duties), but less critical analysis about subsequent events — when security forces joined forces with a crowd attacking the cathedral.

Outside the cathedral later that evening, there was a throng of furious young men attempting to enter through the back door. Every time the door opened, a sea of right arms went up in unison, palms in a fist facing front to show the gatekeepers the crosses tattooed on their wrists.

This was the most devastating sight of the evening, the minority forced to turn in on itself, the confirmation, once again, that behind the one hand rhetoric, sectarianism “runs in Egyptians’ blood” as a friend put it; it is as ingrained in the psyche as the ink in the skin of the wrists going up outside the cathedral.

Inside the church was Abanob, also known as Maradonna, and his friend Bishoy, young men in their late teens. Maradonna immediately enquired about ways of escaping Egypt, routes for emigrating abroad. He talked about his job in Sinai, that “other world” far removed from the rest of Egypt, about his Russian girlfriend Julia. A youth like millions of others in Egypt desperate to flee a sinking ship only with the added sense that he is being pushed overboard.

At the cathedral’s main entrance, a giant poster of the late Pope Shenouda was being carried away for protection. The air was acrid with the smoke from a burning palm tree trunk and lingering teargas. A man on top of the gate leaned against a cross holding a barely legible sign reading, “Our country and we won’t leave it.” Below, a man played Coptic Orthodox hymns on his car stereo and invited people to pray. Around 20 responded to the invitation.

Earlier on, a group of Muslims had prayed inside the cathedral protected by a human cordon of Copts in what is Egypt’s version of “but some of my best friends are [insert minority group here]!”

Rocks and sticks and even a gun were everywhere inside the cathedral, as is perhaps to be expected after the mercurial Interior Ministry proved mysteriously unable to prevent the most important symbol of Coptic Orthodox Christianity in Egypt being attacked, two weeks after it had deployed its impressive armoury to such effect outside the Muslim Brotherhood headquarters in Moqattam.

The interior minister himself turned up at the cathedral over six hours after events began and went on a brief, heavily guarded walkabout. It is not clear whether he ventured into the side streets leading to the cathedral which were covered in broken glass bottles twinkling under the streetlights and where a group of young men were firing starting pistols at some unknown target and the sound of gunfire reverberated through the dark, narrow alleys.

In any case he left, and by the next morning calm had returned, as it always does, and along with it the cathartic escape of explaining away the events as conspiracies and plots. The question of why even if some shadowy, nefarious group is orchestrating sectarian events it finds such an enthusiastic response from ordinary Egyptians is not being asked.