“I am 10 years old, I am Oscar,” begins the first letter of this play of letters. “I didn't know you were there before.”

Oscar writes to God, but he doesn't have the address; he keeps writing anyway, signing off with “until next time.” Oscar is a child with leukemia, bald because of his treatment, played by a bald man, writing in the voice of a child and in the voice of one who knows death is near. The staging, at Rawabet Theater last week, was simple: a bench where Oscar sits and writes, sometimes alone and sometimes with his confidante, Mamma Rose.

We already know who Oscar is. We have been introduced in the prologue. A woman sits on the same bench and writes a letter to Ahmed Harara, the activist who lost sight in one eye when he was shot during the first 18 days of the revolution, and who lost sight in his second eye when he was shot during the November clashes on Mohamed Mahmoud Street. A man, who when he returned from France with the news that surgery would not be successful, was met at the airport by hundreds, and with them, seemingly unfazed, chanted for the end of military rule.

The woman writes to him, struggling for words. She has passed marches on the way to the theater, she writes. The road ahead is long, she knows, but as long as there are heroes like you, Ahmed Harara, she is not scared. She writes that in her quest to find the right words to express all that is inside her, no books or languages could help. In the end, she settles on God. “God bless you,” she writes. And God bless freedom, faith and the homeland. In the word God, she finds all that would be blessed and all that we strive for. We know from her that Oscar lived all his life in twelve days.

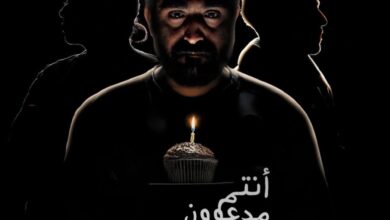

The play, “Oscar and the Lady in Pink,” directed by Hany al-Metennawy, was performed last week as part of the 10-day Combo Mostakil Festival. And although the performances have been put on hold until March in solidarity with the martyrs who continue to fall since the Port Said clashes, the message of the play remains pertinent.

Metennawy's play is based on a novella by French writer Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt published in 2002. It is a series of letters Oscar writes to God. He talks about the woman he calls “Mamma Rose” or sometimes simply “Mamma.” It was she who suggested he write to God. Reluctant at first, soon he finds solace in writing. The roles of Oscar and Mamma Rose are acted beautifully. They move little; their voices, however, sink and soar. We are introduced to a host of other characters, characters we meet only through the letters. At times, there are pictures projected behind the two actors, mostly of young Oscar and the elderly Mamma.

Oscar knows he is dying. He knows that everyone around him also knows. But they don't know how to engage with him. The only person he can talk to is Mamma Rose. One day, he overhears the doctor telling his parents there is nothing more that can be done for him. His parents visit just once a week, unable to express their love for him, unable to speak openly with him, simply bringing him presents. They do not go to see Oscar on hearing the news, and at this moment, he writes, he realizes his parents are cowards, and that they see him as a coward too. He feels utterly alone, aside from Mamma Rose and the letters.

Oscar has just days left to live. Mamma Rose tells him that in the last 12 days of the year, the whole year happens again, each day a different month. Then she suggests to him a game, in which each day is 10 years. After pausing to calculate how much time he has left, he exclaims it would be 120 years. Yes, Mamma Rose says.

Surrounded by an evasion of reality and a fear of confronting his imminent death, Oscar is plagued by isolation and confusion. But in this game, there is something different. It is not a game to avoid reality, but a means to engage with it.

When Oscar is scared to talk to the girl he likes, Peggy Blue, another patient in the ward who is blueish in complexion because of her blood condition, Mamma Rose asks Oscar how old he is. He looks at his watch. Fifteen, he answers her. And she suggests that at that age, he should be braver.

Through the game, he lives a full life in the remaining days of his life, and the 10-year-old Oscar writes to God about his childhood, teenage years, middle age and old age. He loves, he marries. He tells Mamma Rose that he and his wife do all that married couples do — “Of course, I am 30,” he says — and then asks if it is true that Peggy Blue could get pregnant through kissing. It is a humorous and deeply poignant moment, as the naivety of a child and the wisdom that comes with magnanimously facing death collide.

The teens were hard, he writes, the 20s easier. When Peggy Blue leaves the hospital after a successful operation, he knows he will never see her again, “but we lived a good life together.” He is getting weaker; it is harder to write.

Mamma Rose, always in pink, shares stories from her colorful past as a wrestler. They laugh together. She comforts him because she listens to him and answers him. She teaches him compassion for his parents who don't know how to do the same. When he and Peggy Blue could not find the words they wanted in the dictionary — much like the woman in the prologue writing to Harara — Mamma Rose reminds him that sometimes there are not set answers, that there is not one solution to life, but several.

Indeed, living 10 years a day and writing to God was not the solution; it was a solution that gave Oscar a means to live fully as he approached death so young. In the final letter of the play — written by Mamma Rose, also to God, not long after Oscar's death — we learn that it was Oscar who gave her hope and faith in his ability to live and love as he was dying.

Oscar and Mamma Rose teach each other about confronting fear, finding courage, about heroism, about hope and faith, when hope can seem groundless and faith unfounded. And so we the audience are inspired and moved by the journey of a dying boy, and in turn taught about the possibility of heroism, hope and faith when they seem a distant and untenable impossibility.

It is difficult these days not to relate much of what we see, hear and feel to a political context that is, in a sense, all-enveloping. Indeed, the troupe performed the play before the beginning of the revolution, and it was probably a different experience for both actors and spectators.

The troupe added a letter to Ahmed Harara because it is a year of revolution. It is a year of the revolution, and martyrs continue to fall. Victory to the martyrs — as the letter to Ahmed Harara ends — and heroism, hope and faith to all.