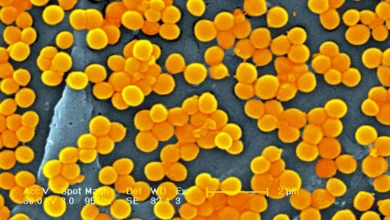

When an illness-causing bug won't disappear with the usual drugs, patients are given last-resort antibiotics such as carbapenem. Still, some "nightmare bacteria" continue to thrive even when given the strongest medicines reserved for the toughest cases.

Carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae, or CREs as they are more commonly know, are a family of germs that are difficult to treat. They tend to spread in hospitals and long-term care facilities, causing an estimated 9,300 infections and 600 deaths each year in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

And they are on the rise.

The genetics of infection

Over a 16-month period, the Harvard-MIT research team examined genetic sequences from about 250 samples of patients who had CRE in four hospitals in Boston and Irvine, California.

"A lot of people have done a lot of really good work by focusing on things like outbreaks," Hanage said. He and his colleagues were aiming instead to get a "population snapshot" of CRE, to define how frequently these infections occurred and to understand which bacterial strains were causing infections within hospitals.

"We tried to get an idea of what the population was, and that enabled us to capture the diversity of these things, which were causing disease in the hospitals we studied," Hanage said.

First, the researchers found very little evidence of direct transmission between patients who became sick. "There's one, maybe two, in all the samples we looked at," Hanage said. Based on this, he and his colleagues believe transmission may be occurring without causing symptoms.

In other words, people colonized with these germs may spread them, a la Typhoid Mary, without ever becoming sick themselves.

According to Dr. Alex Kallen, a medical officer in the CDC's Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion, who was not involved in the study, "the most common source of transmission with CRE is asymptomatic." Most patients will not have any symptoms of CRE, which lives in the gastrointestinal tract, according to Kallen.

The study also documented "the identical gene in different species. … The extent to which this has happened is really quite surprising," Hanage said. Also, "we found two cases of high-level resistance we could not explain."

This he compared to "dark matter: We know it's there because we can see its effects, but what's actually making it happen at the moment is unknown."

"If I were to criticize my own work, I would say it is a shame that we weren't able to get more hospitals and more samples from elsewhere within the health care systems," Hanage said. Limited by funding, the researchers could not track whether transmission had occurred in a long-term care facility or in the community, outside the hospitals they studied.

"These bacteria are deadly. … So we would be well-advised to do everything we can to keep them rare. If we want to keep them rare, we have to understand first how much of them are out there, how many there are out there, where they are and how they're transmitting from person to person," he said.

"The best way to stop a person from dying from this is to stop them from getting sick with this, and the best way to stop them from getting sick with it is to make sure they never pick it up in the first place," he said, adding that "it's incumbent upon us to understand transmission."

The Dutch have one of the lowest rates of antibiotic resistance globally, he noted, because they identify people who are at risk before they come into the hospital.

The importance of handwashing

Though it is easy to feel helpless, each of us can play a role in preventing the spread of these terrifying bacteria.

Hand hygiene and environmental sanitation are essential to preventing the spread of all bacteria, according to Kallen.

See for yourself: A giant petri dish models antibiotic resistance

Giant petri dish helps you 'see' antibiotic resistance

"Make sure people are washing their hands when caring for you. Make sure they are cleaning equipment," he said. Though we may feel at our weakest while staying in a hospital, it is important to speak up if health care providers do not stop and clean their hands.

Chen and her colleagues suggest an approach quite like that of the Dutch, where health care facilities get a history of health care exposures outside their region upon admission, and consider screening for CRE when patients report having visited a place with a higher incidence of CRE.

"Of course, obtaining the history is not difficult, right? It can just be implemented into the intake questions," Dr. Chen said. After Ebola, measles and Zika, many hospitals are already noting travel history during admission.

"For CRE testing/screening, every hospital can do that. It's just a routine bacteria culture first, and then after identifying the organism, they perform the antibiotic susceptibility testing," she said.

Not every hospital has the capacity to detect the exact CRE mechanism. Still, she said, the patient can be immediately isolated while the hospital waits for more advanced results. According to Hanage, the trend is toward using genomics to identify patterns of transmission, the amounts of gene diversity and the presence of resistant organisms.

In 10 years, he imagines a system that is "rapidly taking environmental samples. New threats would be identified and flagged quickly so we can direct our resources most effectively," Hanage said. "In order to be able to do that, you have to know what you are looking for, and so work like this is helpful to tell us what we should be looking for and where we should be worried."