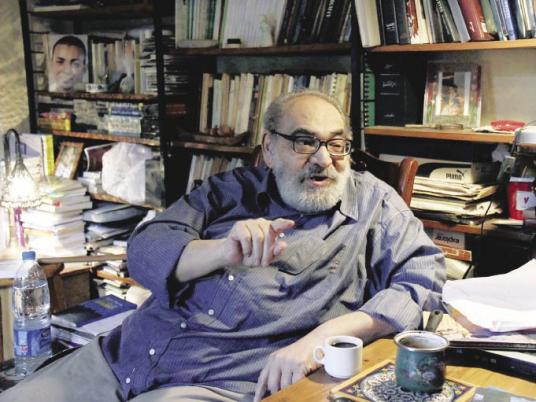

Books of every genre colored the library of novelist Alaa El Deeb, but what immediately caught my attention as I walked into his study was the framed photograph of one of the revolution’s young martyrs, smiling placidly, and a candle with the words “25 January” embossed on it.

The 73-year-old called us from the first days of the revolution, asking for first-hand updates from Tahrir Square and about how the protesters were doing. The sincerity of his tone always struck me; it was as if he knew each and every one of them. He would enthusiastically discuss developments on the ground and celebrate the small victories protesters accomplished every day, with the concern of a farmer for his seedling; he’s been waiting to see this for a long time.

Like Abdel Khaleq al-Messeiry, the protagonist of his 1978 novella “Lemon Flowers” who found new hope in his young nephew, Tareq, Deeb was comforting himself with the outbreak of street protests after many years of disappointment.

He is betting on the youth of the middle class to break the silence and revolt. This was his undisclosed dream, reflected in the first volume of his complete works, recently published by the General Egyptian Book Organization. The collection included his six novellas: “Cairo” (1964), “Lemon Flowers,” “Children without Tears” (1989), “A Moon on Marshland” (1993), “Eyes of Violet” (1999), and “Rosy Days” (2002).

Having experienced the 1952 revolution as a young man, Deeb sees some similarities with the January revolution. He prefers, however, to highlight the differences.

“The 1952 revolution came after long national movements demanding liberation from colonialism,” Deeb tells Egypt Independent. “The writing of the 1936 Constitution was a cornerstone. Then there were the workers and student movements of 1946. So we had a broad range of people engaged with [Egyptian] politics.”

With the January revolution, things are very different. “The land was bare,” and even those who present themselves as opposition had served the regime for years.

Protesters kept demanding and expecting change from those who did not want it to happen, and demands for ideological and cultural changes that entailed communicating with people who had not taken part in the street protests were lost in the middle, argues Deeb.

“[Former President Gamal Abdel] Nasser, on the other hand, was clever enough to promote the 1952 revolution’s ‘philosophy,’ although there was no real philosophy. He cleverly tied the act of revolting to an intellectual process.”

He describes what happened during the 18 days as a “miracle,” and one that was unexplainable.

“So we celebrated it, along with the West as a ‘unique, laughing and peaceful revolution,’ instead of thinking of ways to develop our moves, tools and goals,” he says.

The rebels need to re-present their own ideas and philosophy. The values of the revolution were, unfortunately, killed over the past few months by the ruling military council and others who benefit from the existing regime. People’s demands were described as “narrow,” “opportunistic” and reflective of “special interest groups,” while revolutionaries labeled those who were not immediately aligned with the street movement as the “Party of the Couch.”

“Instead, we need to defend these people’s rights,” he says.

The protesters need to create a new, strong rhetoric, says Deeb, comparing that process to working on a long text or novel, when a writer carefully combines ideas to build a solid framework that many people can engage with.

“Social media networks reach neither the older generations nor the poor. We need to find new ways to communicate and understand each other. Instead, we are being divided even further,” Deeb says.

Deeb has been following the many posts and tweets since the revolution started last year. He was so proud, he says.

“They seemed to be creating their own new rhetoric,” he says. But, he adds, the results of the parliamentary elections proved everyone wrong.

“The short, fractured styles of Facebook posts and tweets are more dangerous to the revolution than its own enemies. … Discussions of ideologies and values become fragmented; they appear suddenly in the form of Facebook statuses and disappear with the same speed. The ideas die quickly because they are isolated, addressing a few people who might already be aligned with these ideas — people you already know — whereas mass media and cultural platforms reach a wide range of people,” explains Deeb.

Many corrupt intellectuals and analysts have declared themselves spokesmen of the revolution in the media, Deeb says, characterizing them as “those who left the streets and went to work for satellite channels.” He advises the revolutionaries to find their place in the media to express and promote their ideologies while continuing to work on the ground through political and social awareness campaigns.

When it comes to developing a platform on which to express those ideologies, Deeb maintains many of his socialist beliefs. He opposes suggestions of privatizing the media and cultural sphere.

“This vision only thinks of the state as a corrupt structure. The state can also face the downsides of free-market mechanisms and provide cultural services to poor people, if it aligns itself with the poor,” he says.

Plus, he says, what the revolution demanded was purging the media of corrupt officials and redirecting the resources to serve the people rather than a particular regime, not just limiting the state’s role to a financier.

The new novel he is working on, “Angels’ Hunter,” maintains a level of pessimism — it tells the story of three old, middle-class, leftist friends, two of whom become opportunistic and ally against the third to hunt him down. But Deeb remains optimistic about the revolution.

“My protagonist represents me and my time, so we share the same fate,” he says.

But he thinks the revolutionaries will have a different fate.

“They’ll be able to get their rights in their own way,” he says.