Although the Khaled Saeed case was covered by Egyptian newspapers, it was the post mortem photo of his maimed corpse – a shattering proof of police brutality – that really moved the public, and it was later identified as a major catalyst of the 25 January revolution.

Photographs are both triggers and symbols of change; and the extensive coverage of the Arab revolutions by mainstream media worldwide is building a new collective image of Arab countries and their people.

The self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi spurred thousands of outraged protesters to defy police forces and take to the streets in Tunisia. In turn, images of demonstrating crowds pushed people to follow suit and support the uprisings, while reports on the violent crackdown on demonstrators, prompted worldwide indignation.

“The images we saw of the Tunisian protests pushed the revolution here, even though discontent was being increasingly manifested since 2005,” said Egyptian blogger and activist, Rami Raouf, adding, “I wouldn’t say it wouldn’t have happened otherwise, but still, the images had the power to galvanize the Egyptian people.”

Despite its obvious impact, photojournalism as a discipline is in crisis globally. Hundreds of photojournalists were sent to Haiti in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake, yet photographic coverage was both sensational and redundant. Even when photographers sought to reflect a human face of the catastrophic event, only the most sensational pictures made it to the front pages of newspapers.

But the situation in the Arab world is more complex, as photojournalists face a series of challenges on institutional, disciplinary and political levels.

The challenge of impartiality

While photojournalism is an established profession internationally, in the Middle East the job is laden with contextual limitations and many photojournalists simultaneously act as reporters and “semi-activists”.

The camera’s lens can provide a voyeuristic shield, allowing photojournalists some distance from the events by focusing on technicalities. It is often, however, deployed as a tool of dissidence.

The decision to distance oneself for the sake of “telling the truth” is not automatic, explains Yemeni photojournalist Jameel Sebay. “I didn’t even want to distract myself. I just wanted to be with them [the demonstrators] and enjoy the revolution, watching an old man sing with his guitar on a makeshift stage to an audience of 20 people. I was witnessing small revolutions on every corner. That’s the memory I wanted to capture – not the close-ups of politicians that earn me a salary.”

This contentious position of Arab photojournalists needs to be contrasted with the outsider perspective of foreign journalists who often “parachute” into the middle of the action without sufficient knowledge of the sociopolitical background. To compensate for that, they rely heavily on various mediators such fixers, drivers, assistants and above all translators. While they sometimes add a different perspective by highlighting details of daily life often overlooked by locals, in many cases, they fall into the trap of exoticism.

With access being key to the profession, much is lost in the mediation, and in many cases photographic narratives conform to mainstream criteria of sensationalism, controversy, clash, violence and suffering.

Selection of images is carried out by the major news agencies that distribute them around the world. Hence, the narrative seems to be monopolized by a “globalized” and often simplified visual representation.

Escaping stereotypes in the news business

Thanks to the proliferation of amateur photography, backed by the availability of affordable photographic equipment, newsrooms now have access to a much broader photographic archive. Citizen journalists, activists, tourists and travellers are increasingly engaging with photography, allowing cost savings on the part of newspapers who no longer have to pay for travel, insurance and collateral expenses in advance. But, this makes it more difficult for photojournalists, especially in the Middle East, where photojournalism features low in the newsroom hierarchy and is seen as a complementary element to textual reporting.

In Yemen and Algeria, for instance, photojournalism is not even considered a profession and editors simply download pictures from the internet. Newsrooms seldom have a budget for photo shoots and editing, and individual expression is hampered by market pressures to compete with big agencies.

Photojournalists mostly have no control over the use of their images after selling them to agencies, and many are anxious about presenting a distorted version of reality, should their photographs be wrongly contextualized.

Fifteen photojournalists from Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Yemen, Jordan, Iraq and Kurdistan expressed their anxiety over the topic during “Investing in the Future” workshop hosted by Cairo’s Contemporary Image Collective in May.

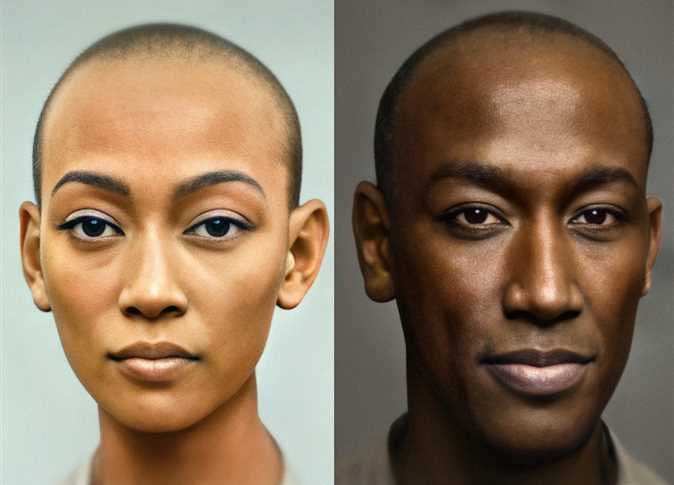

Most of them had covered demonstrations in their countries and were challenged to cut down the clichés that make the revolution less “visually interesting”. Mainstream media has been saturated with images of coffins, raised fists, crying veiled women, poorly equipped rebels, crowds photographed from above, flags, un-translated banners, blood, bullets and clashes with security forces.

The problem is that only pictures that fit into a specific framing of “the other” are accepted, even if they are stereotypical. To be part of the market, photographers have to adapt to such clichés.

But is it possible to fight prejudice and stereotypes by presenting a personal view?

Claudia Hinterseer, the director of Noor Photo Agency, believes so, arguing that, “reality is rich and layered. You can tell the same story using different words. You have to enrich the photographic language with your personality.”

Egyptian photographer Miriam Abdelaziz, however, says, “By the time one develops quality material for a story, it’s already too late, and nobody is going to cover photographers’ costs in advance.”

“But images that don’t seem interesting now could become very emblematic within a few years, depending on how things develop,” points out Noor photographer Alixandra Fazzina, adding that Arab photojournalists have a responsibility to archive documentary photographs for future generations.

Competition or collaboration with social media?

On 26 January, Egyptian state-run media made no mention of the 25 January protests. “It was images of violence circulating online that spurred many people to take to the streets and witness the events that the government was trying to hide and manipulate,” explains Abdelaziz.

In the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions, photojournalists were eager to put their pictures online and make them available to the public, without having time to worry about copyright protection. Their activism often preceded their role as photographers.

Rather than being a question of competition between professional photojournalism and user-generated content, it’s been more of a collaboration, in which social media helps fill the gaps in traditional news media.

“In Bahrain, for example, there are so many restrictions that it’s impossible to work outside of news media. Facebook is a social tool. But when media doesn’t function the way it should, social media takes over, becoming a tool for lobbying influence,” explains Algerian photographer Mohamed Messara. In Syria, there are no international journalists, and local ones have been jailed or face death threats, so even Al-Jazeera has to rely on citizen journalism.

In Cairo’s Tahrir Square, activists set up three media tents, with technicians and programmers volunteering around the clock. It was a spontaneous network of collaboration facilitated by the common goal of passing the information to people. Their proximity to the center of events allowed them to verify information that would be amplified by social media.

These collaborative processes earned bloggers and online media credibility worldwide. Everyone contributed to the narrative, with blogging and social media promoting criticality. People would not only carefully criticize the news but also the way stories were told.

These times offer an opportunity to rethink both the role of photojournalism as a discipline and the role of images in forming public perception. Towards the end of the "Investing in the Future" workshop, participants, made a number of propositions, including sharing sources between photojournalists and writers, providing photography training for journalists, as well as encouraging investigative reporting and expanding photographic archives. Establishing an Arab network for photo agencies also seems to be important, as well as forming a network of national observatories for photojournalism. Such networks would promote best practice and report violations. But the public also needs to actively exercise its right to be informed.

Rather than a struggle to impose “an alternative view” of the region, photojournalists want to include a plurality of voices, to counter the risk of images being used to reframe the region back to the common image of “instability and chaos".