There is little of the quiet contemplation or stillness that often accompanies art events. On Lazoughly Square around the corner from the Interior Ministry, video works are shown on a small TV screen against the backdrop of a closed-down branch of the popular fast-food chain Gad. People come and go, some smoke, others drink coffee, and, from time to time, a local resident walks in front of the screen, laden with shopping bags.

The question has been posed before: Does a piece of art change with its setting? The relationship a viewer forms with a piece of art is both personal and social, and informed by a number of factors, not least of which is place. Watching “Without Cover” by Ibrahim Saad, in particular, in the setting of an evening of public screenings, gives it a resonance it might not have had otherwise.

A split screen: on one side, famous scenes from Baghdad of the face of a Saddam Hussein statue being covered with an American flag and then being toppled. These emblematic images, apparently of throngs of joyous Iraqis spontaneously bringing down a symbol of their former dictator, turned out to be staged by the US military. The images on the right side of the screen show the covering of the face of a statue of novelist Naguib Mahfouz with an Egyptian flag, following the national team's defeat at the hands of Algeria. This was also staged, but in a different way; it was staged because such an act depends for its meaning on spectators, on being seen.

In a way, politics is performance and spectacle. (Much ink has already been spilt on the performative aspect of demonstrations in Tahrir Square, and no doubt there is more to come.) The staging of art in public spaces is also both performance and spectacle. And it is deeply political, coming as part of a trend of reclaiming public space as a zone of freedom, standing opposed to the disciplining of space by the Emergency Law and security dictates. There was something of the spectacle in the event, made all the more so by pantomime artist Amr Abdel Aziz, one of the Mahatat collective, responding to some of the shots and scenes.

Throughout the evening, 17 pieces of video art were shown by both established and emerging artists, the majority from Egypt but also from across the Arab world. Yara Mekawei, artist and curator, had the idea of public screenings of video art over a year ago, but it was when she came across Mahatat, a multi-cultural art initiative founded in 2011, that the screenings became a reality. She shares with Mahatat the idea that art should not be confined to galleries and art spaces, where the same people come along. Rather, they seek to break down the barriers that inhere in this model of art practice and to bring art to the public, to transform any space into an art space.

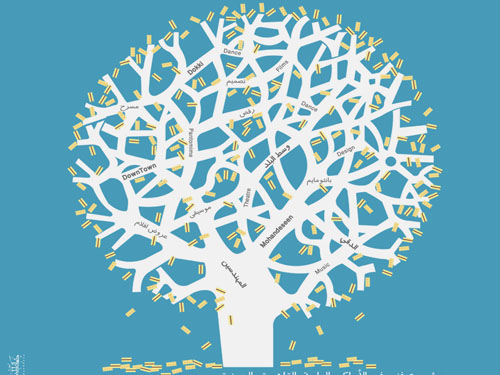

The name of the Mahatat initiative, of which “Public Screen” is a part, translates as "our streets" — which reflects this principle and mission. “Public Screen” is the second part of Mahatat; the first was pantomime on Cairo's metro earlier this year, and still to come are contemporary dance workshops and flash mobs, and a participatory art project centered around trees.

Immediately in front of the TV, familiar faces from Cairo's art circuit are seated, standing and crouching. Forming an outer circle, people from the neighborhood stand, sit on a fence, or lean on cars. A couple of policemen passing by also stop to watch. Rather than simply a reclaiming of public space for art, users of this piece of public space this evening segregate themselves. Perhaps this is too strong a word; we should say they organized themselves.

Do passersby stay for the most part on the outskirts because they feel uncomfortable getting closer? Meanwhile, other locals are unfazed and simply walk in front of the screen with their shopping; living in the shadow of the Interior Ministry, they are probably used to all kinds of disruptions. Does the usual art crowd sit in the inner part because they feel more comfortable and confident in claiming the space? Or perhaps passersby stay on the outskirts not because they are uncomfortable, but because this gives them the autonomy and freedom to leave easily when they want to.

Indeed, a number of people come and go, and several passersby pause and look before moving on. The success of such an event need not be judged by how long people stay. The very fact that someone on the way home sees a familiar space used for an unfamiliar purpose may itself be enough.

“Transparent Black” by Shayma Kamel, a creative meditation on the struggle to deal with the ways in which society constructs the female body, begins with tomatoes bouncing around before being squashed to a pulp. Pantomime artist Abdel Aziz recoils and winces as the tomatoes are crushed. The piece moves on to images of a woman's body. While not overtly sexual, these images appear to make some uncomfortable. One passerby who has seemed quite engaged with the scenes of the tomatoes leaves quite quickly at this point; another curious older passerby stops to see what is happening and, on seeing a close-up of a woman's legs, walks away.

Though an open call was sent out particularly for this initiative, it was unclear whether the curatorial choices were any different from what they may have been for a more conventional event. The choice of a film showing a part-naked female body seems like an odd one if the aim is to attract people who would not usually engage with this kind of art. Curating for this kind of event necessitates different decision-making, unless the aim is to shock, or perhaps if a commitment to freedom of expression leads one to believe that choosing not to include a film like this constitutes an act of censorship.

The combination of images such as those of the woman's legs with the fact that the subtitling in some of the films does not work means that someone passing by may find it difficult to engage. It is unfortunate, for instance, that in the opening shot of “Beard Burn” by Edward Salem, the words “Homage to Mohamed Bouazizi” appear only in English. The choice of some of the films in languages other than Arabic also adds to the impression that this is a gathering of foreigners, something a few passersby comment on.

Though she does not stay to watch, one local resident says this is more interesting than the soap operas and news continuously on television. Mahatat's vision is a world where contemporary art forms an integral and visible part of everyday life. Screenings such as “Public Screen” are one part of a broad process whereby we may get closer to such a vision being a reality and closer to inhabiting the streets as truly ours.

There will be more public screenings of film and video art over the next month:

18 March at 7 pm on Alfy Street, Downtown

25 March at 7 pm in Mesaha Square, Dokki

1 April at 7 pm on Gamaet al-Dowal, between Batal Ahmed Street. and Geziret al-Arab Street, Mohandiseen

The film program will be available beforehand on Mahatat’s website and Facebook page.