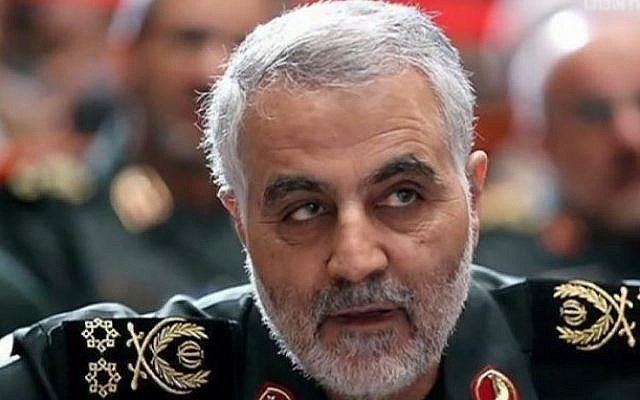

(Reuters) – Qassem Soleimani’s role in a political crisis in Iran highlights the influence of the leader of the Revolutionary Guards’ Quds Force, who has acquired celebrity status at home after being largely invisible for years.

The resignation of Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif last week was quickly rejected by President Hassan Rouhani, but a week on, tension over Zarif’s absence from meetings with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad that Soleimani attended is still evident.

Soleimani’s Quds Force, tasked with carrying out operations beyond Iran’s borders, shored up support for Assad when he looked close to defeat in the civil war raging since 2011 and also helped militiamen defeat Islamic State in Iraq.

Its successes have made Soleimani instrumental to the steady spreading of Iranian influence in the Middle East, which the United States and Tehran’s regional foes Saudi Arabia and Israel have struggled to keep in check.

Khamenei made Soleimani head of the Quds Force in 1998, a position in which he kept a low profile for years while he strengthened Iran’s ties with Hezbollah in Lebanon, Assad’s government, and Shiite militia groups in Iraq.

In the past few years, he has acquired a more public persona, with fighters and commanders in Iraq and Syria posting images on social media of him on the battlefield, his beard and hair always impeccably trimmed.

“Soleimani is an operational leader. He’s not a man working in an office. He goes to the front to inspect the troops and see the fighting,” said an Iraqi former senior official who asked not to be identified discussing security issues.

An Iraqi militia released a music video in 2014 praising Soleimani’s efforts in fighting Islamic State, and state media have run multiple accounts of his role in military victories.

“His chain of command is only the Supreme Leader. He needs money, gets money. Needs munitions, gets munitions. Needs materiel, gets materiel,” the Iraqi former official said.

After Zarif tendered his resignation, Soleimani issued a rare statement. There had been a “bureaucratic” mistake rather than any intention to exclude Zarif, it said, describing the minister as the main person in charge of foreign policy and backed by Khamenei.

But on Tuesday, the Iranian Students’ News Agency (ISNA) reported that the foreign ministry had not been informed throughout Assad’s trip, citing ministry spokesman, Bahram Qassemi, saying Zarif’s aim with his resignation was to restore Iran’s diplomatic system to its rightful place.

“WE ARE CLOSE TO YOU”

The row is an unusually public display of tension between the Guards, who play a key role in politics in the Islamic Republic, and moderate government officials who favor reconciliation with the West 40 years after Iran’s 1979 revolution ousted the US-backed Shah.

A regional official with knowledge of Iranian affairs said the foreign ministry and the Quds Force had conflicts of opinion over Syria. The release on Monday of a closed-door speech last year by Khamenei highlighted another ongoing split – over Iran’s agreement with world powers to curb its nuclear program in return for sanctions relief.

The speech voiced doubt about the government’s overtures to Europe to try to shore up the deal after US President Donald Trump pulled out.

A major-general, Soleimani is also in charge of intelligence gathering and covert military operations carried out by the Quds Force and last summer he publicly challenged Trump.

“I’m telling you Mr. Trump the gambler, I’m telling you, know that we are close to you in that place you don’t think we are,” said Soleimani, wagging an admonishing finger.

“You will start the war but we will end it,” he said, with a checkered keffiya draped across the shoulders of his olive uniform.

“GETS WHAT HE WANTS”

Softly-spoken, Soleimani came from humble beginnings, born into an agricultural family in the town of Rabor in southeast Iran on March 11, 1957.

At 13, he traveled to the town of Kerman and got a construction job to help his father pay back loans, according to a first person account from Soleimani posted by Defa Press, a site focused on the history of Iran’s eight year war with Iraq.

When the revolution to oust the Shah began in 1978, Soleimani was working for the municipal water department in Kerman and organized demonstrations against the monarch.

He volunteered for the Revolutionary Guards and, after war with Iraq broke out in 1980, quickly rose through the ranks and went on to battle drug smugglers on the border with Afghanistan.

“Soleimani is a great listener. He does not impose himself. But he always gets what he wants,” said another Iraqi official, adding that he can be intimidating.

At the height of the civil war between Sunni and Shiite militants in Iraq in 2007, the US military accused the Quds Force of supplying improvised explosive devices to Shiite militants which led to the death of many American soldiers.

Soleimani played such a pivotal role in Iraq’s security through various militia groups that General David Petraeus, the overall head of US forces in Iraq, sent messages to him through Iraqi officials, according to diplomatic cables published by Wikileaks.

After a referendum on independence in the Kurdish north in 2017, Soleimani issued a warning to Kurdish leaders which led to a withdrawal of fighters from contested areas and allowed central government forces to reassert their control.

He was arguably even more influential in Syria. His visit to Moscow in the summer of 2015 was the first step in planning for a Russian military intervention that reshaped the Syrian war and forged a new Iranian-Russian alliance in support of Assad.

His activities have made him a repeated target of the US Treasury: Soleimani has been sanctioned by the United States for the Quds Force’s support for Lebanon’s Hezbollah and other armed groups, for his role in Syria’s crackdown against protesters and his alleged involvement in a plot to assassinate the Saudi ambassador to the United States.

Soleimani’s success in advancing Iran’s agenda has also put him in the crosshairs of regional foes Saudi Arabia and Israel.

Top Saudi intelligence officials looked into the possibility of assassinating Soleimani in 2017, according to a report in the New York Times late last year. A Saudi government spokesman declined to comment, the Times reported, but Israeli military officials have publicly discussed the possibility of targeting him.