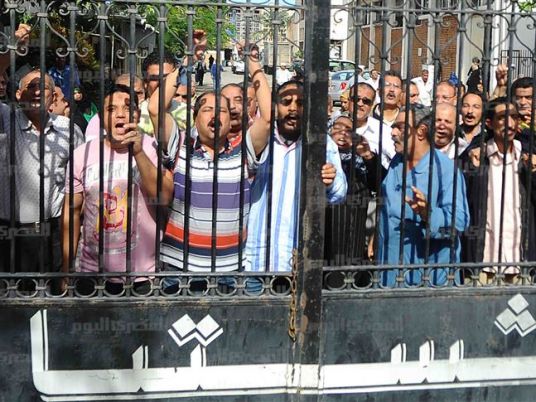

Time and time again, officials have accused ongoing protests, workers’ strikes and labor action of halting the so-called wheel of production. The counter argument has also been reiterated, attributing the ailing economy to the government’s myriad bad decisions and their mismanaged implementation.

Production implies industry, and industry refers to the thousands of factories in Egypt, all of which have suffered in one way or another as a result of an economic slowdown, a mounting funding crisis on the national level, diminished foreign reserves and feeble capital inflows.

The dynamic only exacerbates already existing problems in the country’s industrial sector, incurring further discontent among workers. These sector-specific troubles are reflective of, and further compounded by, broader economic turmoil.

Since the January 2011 uprising, at least 4,500 factories have been shut down, with hundreds of thousands of workers laid off, according to a study conducted by a labor rights group in February.

As Egypt’s dire economic conditions worsen, further closures and layoffs are expected.

The study by the Center for Trade Union and Workers’ Services, or CTUWS, an independent NGO, was conducted in 74 industrial zones across the country. In terms of the effect on joblessness, the findings appear to correspond with official statistics compiled by the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics.

The agency’s statistics indicate that Egypt’s unemployment rate has risen to a record 13 percent, roughly 3.5 million people from a total workforce of some 27 million.

Adel Zakariya of CTUWS says hundreds of thousands of workers have been rendered jobless since the onset of the revolution. While an exact number is tough to determine, he says the mass of layoffs is “unprecedented.”

“The exact number of sacked workers is difficult to gauge at any given point of time. For example, we find that sacked workers from a certain food-processing company may relocate to another such company within the same industrial zone in which they worked,” he says. “A lack of employment contracts and masked or seasonal unemployment make it nearly impossible to assess the exact numbers of unemployed workers.”

More, not less

Nearly all factories that have been shut down since the revolution are private-sector companies, Zakariya says. “We’ve witnessed partial company closures, including the closures of some factories and production lines within these companies, along with total company closures.”

While he recognizes that there were hundreds of factory closures during former President Hosni Mubarak’s rule, the “rate has increased exponentially since the revolution.”

The 4,500 factory closures cited in the study is not comprehensive; it is a result of the number of factories surveyed in industrial zones that the CTUWS has been monitoring. The actual sum, Zakariya predicts, is likely significantly higher.

“Numerous different industries have been hit by these closures. Perhaps the hardest-hit industry is textiles,” he says, though “the textile industry has been in a steady state of decline since Mubarak.”

A combination of mismanagement, corruption and indebtedness of public-sector textile companies led to broad privatization measures in the early 1990s. Dozens of these companies slashed the workforce they inherited from the public sector, and, after their privatization, appear to have been similarly mismanaged.

The Cairo Administrative Court nullified some privatization contracts over the past two years, leaving companies such as Indorama Shebin Textile, Nile Cotton Ginning, and Tanta Flax and Oils in limbo, as the state has declined to re-nationalize them.

The steady decline of Egypt’s cotton industry also prompted the import of lower-grade cotton, leading to a deterioration in the quality of domestically manufactured textiles. In turn, hundreds of thousands of textile workers have been rendered jobless, while more recent economic factors threaten to further increase unemployment rates.

The textile industry has suffered most in the private-sector industrial zones of Sadat City and 10th of Ramadan City, while metallurgical industries have been impacted most in Obour City.

Financial obstacles

The surge in the number of factory closures is attributed to factors that have impinged on the economy at large. Zakariya cites “difficulties in procuring financing and bank loans, which have in turn negatively affected production and exports, along with some capital flight from Egypt amid the climate of political instability in the country since the revolution.”

Industry insiders and bankers have cited a shortage of dollars with a depreciating pound and scarce foreign reserves as reasons for the banking sector’s increasing hesitancy in providing funding and lines of credit. This affects the ability of ailing companies and factories to obtain rescue loans or financial support, and also stymies the import-export flow of goods.

Zakariya admits that financial problems may be compounded by workers’ strikes and industrial actions. “But although strikes do negatively affect production, these industrial actions are at the bottom of the list of factors leading to factory closures,” he says.

A statement issued last month by Finance Minister Morsy Hegazy said Egypt incurs losses of about LE100 million per day due to labor strikes and political unrest.

One private-sector company with a number of factories blames industrial action for its problems, and last month its owner took drastic measures to make his point heard.

Farag Amer, chairman of the Faragello Food Industries Company board of directors, wrote a widely circulated statement in late February accusing President Mohamed Morsy’s regime of failing to respond to what he called “blackmail and the moral deviance” of workers, who launched “unwarranted strikes in contravention to the provisions of law.”

On 20 February, Amer imposed a lockout, and shut down his factories across the country following industrial action by workers in Alexandria.

The Faragello administrative board ordered the sacking of 27 striking workers, including 17 union leaders, according to workers and independent union organizers.

A senior administrator from the Faragello company, who spoke on condition of anonymity, tells Egypt Independent, “We’re back to operations as usual. All our companies and factories across the country have returned to work.

“We had shut down operations for only a few days in light of the illogical demands raised by newly employed workers, calling for unrealistic bonuses and pay raises,” he says, but did not comment on the dismissal of unionists and striking workers from the company.

But Zakariya says political as well as financial factors motivated the temporary closure. While it’s not clear what the company owners’ affiliations are, they appear to be seeking Morsy’s intervention in dealing with striking workers and independent unionism in their company.

“Faragello’s administration is involved in a game of political maneuvers with the new regime … playing its political pressure cards with the regime, because they want to eliminate strikes and independent labor unions,” he claims.

The Faragello administrator went on to say, “We demand security and stability for our industries, and for the country as a whole.”

However, he adds, the company may deal with problems such as lack of diesel and fuel to power the factories in the future.

Egypt’s diesel crisis has extended far beyond affecting drivers and causing winding traffic jams around gas stations. It is now halting work at some factories, disrupting transportation of school buses and, more critically, failing to meet the needs of power plants as the heavy energy-consuming summer months approach.

“Given the national outlook for diesel and fuel shortages, along with associated electricity blackouts, we are expecting additional factory closures and even more layoffs. Whether these closures will be permanent or temporary, partial or complete, we’ll have to wait and see,” Zakariya says.

Factories in Sadat City and 10th of Ramdan are edging closer toward possible closures due to the diesel crisis, he adds.

Government response

Government officials have attempted to address the numerous factory closures, while simultaneously proposing plans to create thousands of new jobs. On 6 March, the Cabinet claimed the government helped secure 522,000 job opportunities, including 345,000 locally and 177,000 for Egyptians abroad.

In a televised interview 25 February, Morsy said 119 new factories commenced operations in Egypt that month, with about 300 more factories in the pipeline. The Finance, Manpower, Investment and Youth ministries proposed an ambitious plan to jointly create 700,000 new jobs this year.

However, union organizer Tallal Shokr, board member of the Egyptian Democratic Labor Congress, is skeptical of these grand proclamations.

“The government claims that it has secured hundreds of thousands of job opportunities for Egyptians, and claims that it will create hundreds of thousands more — these are baseless claims, merely for media consumption,” Shokr says. “The reality is that unemployment has reached a record high, and new job opportunities are not being provided, at least not on the scale that the government is claiming.”

He cited as further setbacks the state’s move toward cutting public spending in an attempt to rein in the widening deficit, as well as plans to curb subsidies and a number of expected measures associated with the US$4.8 billion International Monetary Fund loan being negotiated.

“In light of current economic conditions, the government will not be able to provide the 700,000 new jobs that it speaks of. The best it can do is to provide contracts for those who are already employed and claim that they have created all these new jobs,” he adds.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.