Baghdad– The US ambassador to Iraq outlined twin challenges Monday to the unsteady democracy’s elections next month: assuring that voters and rival factions accept the result and then making sure the losers step aside quietly.

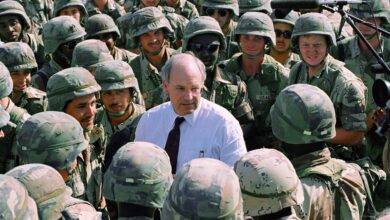

Christopher Hill said the 7 March parliamentary balloting will likely shape Iraq’s path long after the US military pullout. It also will test Sunni-Shia cooperation to quell violence–which struck again Monday as a suicide bomber killed at least 54 Shia pilgrims.

The vote, delayed from January, will be the last major election in which the US military is helping with security. At stake are some of the country’s most ambitious goals, including political and sectarian reconciliation and finalizing a law governing the oil industry, on which Iraq’s economy is almost solely dependent.

In an interview with The Associated Press, Hill said he was confident Shia political leaders would soon settle a seething debate over the purge from the ballot of about 450 candidates accused of being loyalists to Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime. The blacklist is widely seen as targeting Sunnis, even though Shia candidates are also on the list.

He predicted the Iraqi government would fully explain the reasons for banning each of the candidates because "there should be a situation where people don’t scratch their heads at why certain people have been included on the list."

"We don’t want a situation where some people, or some groups of people, do not accept the outcome" of the election, he said. "That can make the security situation problematic."

Among those barred from running is prominent Sunni politician Salah al-Mutlak, who has acknowledged he was a Baathist until the late 1970s, when he quit the party. An Iraqi court dismissed al-Mutlak’s appeal and 41 others this week, said Hamdiya al-Hussaini, a member of the independent elections commission. A clear reason why was not immediately available.

A high-profile sheik in Anbar province, Awakening Council leader Ahmed Abu Risha, is weighing whether to urge fellow Sunnis to boycott the election if the purge continues. His group was one of the first of Sunni insurgents to side with U.S. forces against Al-Qaeda.

A perception among Sunnis that they are being shut out of the election could set back progress the US military made in 2006 and 2007 in reversing the insurgency, which threatened Iraq with civil war. A breakdown in security could also hamper US plans to withdraw all combat troops by the end of August, a move that is critical to President Barack Obama’s new focus on Afghanistan.

Violence has ebbed substantially across Iraq over the last two years. But in a grim and all-too-familiar reminder of sectarian attacks, Iraqi security officials said a female suicide bomber who hid explosives beneath her long black abaya cloak killed at least 54 people in Baghdad on Monday as Shia pilgrims headed to the southern city of Karbala ahead of a Shia holy day.

Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki has staked his political future on an alliance with fellow Shia and moderate Sunnis–all seeking to portray themselves as reliable leaders by citing improvements in overall security and hints of economic gains such as recent oil deals with foreign investors.

But al-Maliki faces Shia rivals from among religious parties and from his own interior minister, who has forged a bloc with the Sunni sheikh Abu Risa.

In his embassy office in the Green Zone, Hill spoke of what he called "the day after"–the transition into the new government’s rule. He predicted it will "take a lot of time" for the government to get up and running–mostly to ensure balance and inclusion among competing political forces.

After Iraq’s last parliamentary election in 2005, bickering between and within political parties and religious groups delayed the new government from being seated for months. Part of that was because of US insistence that Sunni lawmakers be given some power to balance out majority Shia leaders.

If the ballot purge leads to disputed election results, the government could be delayed even longer. International election observers believe a disputed election that leads to chaos could easily inflame insurgents who already have sent political messages in the forms of car bombs and suicide bombers to target government buildings in four spectacular attacks in Baghdad since August, including one last week.

"What will help determine whether these elections are successful or not is not the behavior of the winners, but rather how the losers accept the elections," Hill said.