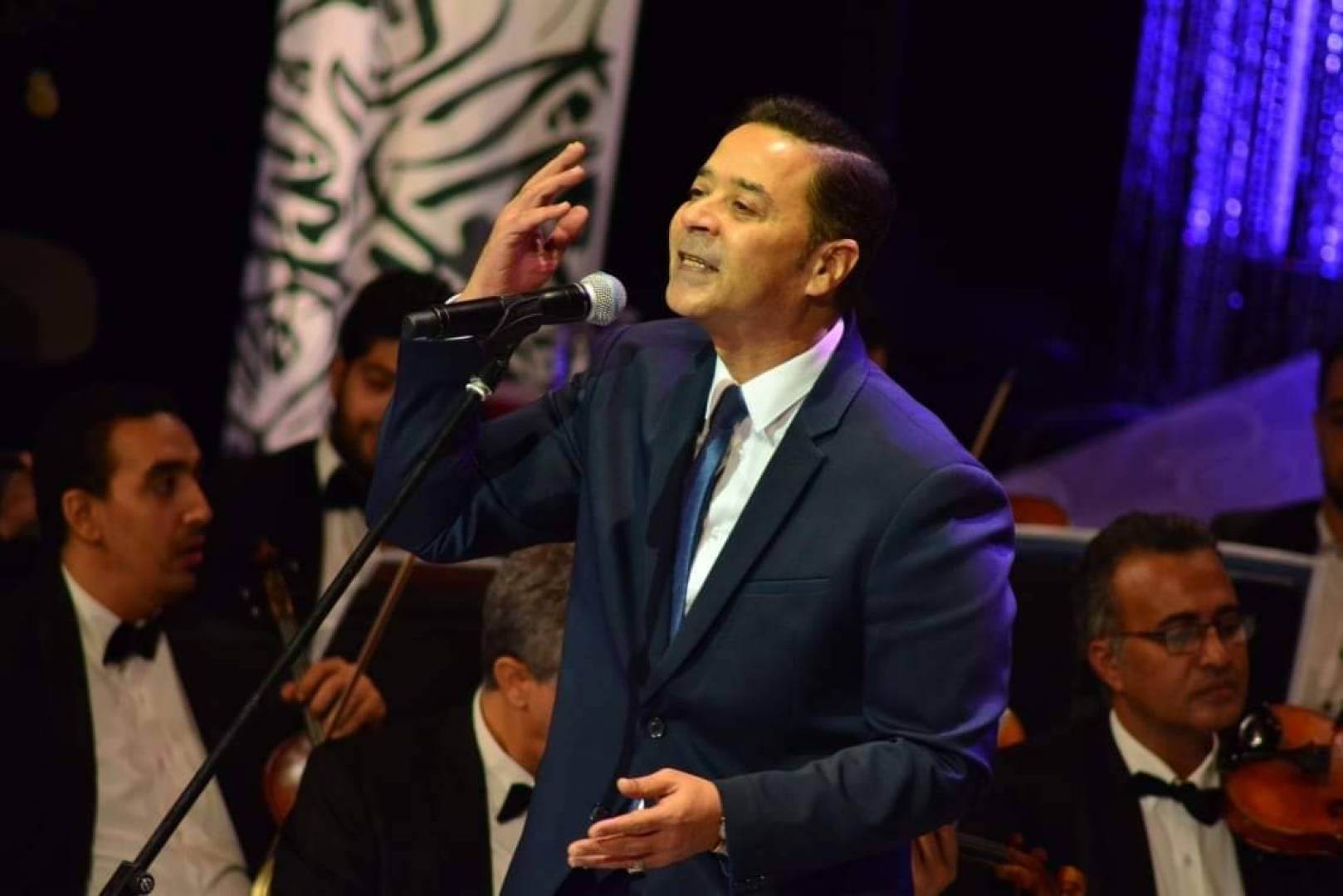

It seems that some people are now betting on the 1970s generation of intellectuals, promoting independent projects, for “it is they who protected the country over the years and acted as its safety valve with their awareness and insistence on success in the face of a deluge that struck everything,” as Shaker Abdel Hamid, the newly appointed secretary general of the Supreme Council of Culture, puts it.

Abdel Hamid belongs to this generation that he says “has been repeatedly wronged, but never corrupted.” He specialized in creative psychology, and has written several books about theories of arts and creativity, including “Creativity and Insanity” in 1993, “The Age of the Image” in 2005, “Visual Arts and the Ingenuity of Perception” in 2007, and “Arts and Oddity“ in 2010.

He was vice president of the Arts Academy in Egypt between 2003 and 2005, before moving to Bahrain to direct the talent development program at the College of Graduate Studies of the Arabian Gulf University, until 2011. He currently teaches creative psychology back at the Arts Academy.

Only a few days after he assumed his position at the council, Abdel Hamid was put in charge of the fine arts sector, after the ministry failed to find a replacement for former head, Ashraf Reda.

He also had to participate in debates shaping Egypt’s cultural future, mainly the final vision about the relation of the council to the Culture Ministry. Intellectuals have repeatedly accused the council of corrupting cultural life and compromising them. As Farouk Hosni, Culture Minister under Mubarak’s regime for 24 years, repeatedly said: “I’ve brought intellectuals back to the barn.” Many intellectuals currently demand separating the council from the ministry and transforming it into a cultural fund and independent authority that monitors the ministry’s performance.

Al-Masry Al-Youm: What do you think of this step?

Shaker Abdel Hamid: More discussions are needed among intellectuals before a decision to separate the council from the ministry is taken. A new strategy for the council and for culture in general needs to be developed. The council plays an important role in cultural life along with other institutions, both within and outside the ministry. So we cannot take a hasty decision that might compromise the integration between the ministry’s cultural institutions, and also, with the ministries of education and information, which play an equally important role in cultural development.

The council does not set a cultural vision for intellectuals alone, but for all Egyptians. We cannot separate ourselves from reality, and the public’s orientations.

Al-Masry: Are you suggesting creating an authority that oversees all three ministries you just mentioned?

Abdel Hamid: I am not suggesting monitoring tactics, but rather participation and guidance among all three institutions and this cannot happen until a future vision for the country as a whole is developed. No one knows yet who will come to power and what plans they might have for Egypt.

Al-Masry: Are you saying that the decision about the future of the council should be postponed until intellectuals decide on this step? A two-day workshop was held in the council and a plan was drawn, so what will you do with this plan?

Abdel Hamid: Artists Adel al-Siwi and Hazem al-Mistikawy proposed more than one vision, favoring the separation. However, others expressed their concerns about this step, like former secretary general of the council, Ezz Eddin Shokry. A draft of the various propositions, highlighting their pros and cons, has been submitted to the culture minister.

Al-Masry: But, do you see the separation scenario as plausible?

Abdel Hamid: Yes, but in a later stage. Proper legislation needs to be devised to regulate the work of various institutions, and all this should be discussed for a long time. We are now in a transitional period, when it is difficult to make such important decisions.

Al-Masry: What is your vision for the council over the coming period?

Abdel Hamid: I see the council as a garden that includes different but harmonious elements. This garden can be either closed or open; and I prefer to have it open onto society, reflecting the various social trends.

Our role is to encourage everyone to follow his or her creative endeavors. People need their work to be published; they need bursaries and awards; it’s our way to support them. But this needs proper regulation.

Al-Masry: Opening up the council for all trends, to use your expression, might bring in younger intellectuals with fanatic ideologies and limited intellectual production. And this argument was often made by the council to justify excluding younger generations. Free verse writers, for instance, were excluded from the council, because Ahmed Abdel Mo’ty Hegazy, head of the poetry committee, did not recognize free verse as an art. On the other hand, novelists – regardless of the quality of their work – were welcomed into the council. So how will you strike a balance in this?

Abdel Hamid: I believe younger generations should be welcomed more into the council. But this should happen through proper criteria and selection mechanisms. Why would the council accept members with no intellectual production in its committees and activities? The important thing is to have continuous change in the council’s committees so they are not restricted to older generations. We are currently discussing a mechanism that would allow independent cultural institutions to nominate candidates for the council’s committees instead of current members repeatedly re-nominating themselves; this has long restricted membership to particular groups from a single generation of intellectuals.

Al-Masry: The council was established in the absence of a Culture Ministry in 1956. It was called the Supreme Council for Arts and Literature. Then, the ministry was reinstated in 1980. Instead of canceling the council, it was renamed with minor changes in its function. The argument at the time was that it would have a new role: overseeing the performance of the ministry, although the council’s secretary general remained the minister of culture. This contradiction triggered much criticism among intellectuals, accusing it of “compromising intellectuals.” In your opinion, what role should the council play in the upcoming period if it is not separated from the ministry?

Abdel Hamid: Its aim is to support creative workers. It should not influence intellectuals’ ideas in the upcoming period. No true intellectual would accept that, because being free and independent is part of the intellectual’s formation. The council’s role is to help them attain that.

Al-Masry: Do you see the council’s separation from the ministry leading to separating other sectors in the ministry and turning them into funds that support independent projects? This vision is advocated by many, who believe that the state’s role should be confined to providing services like education and healthcare, while the cultural field should be managed by independent institutions.

Abdel Hamid: Of course all institutions can separate from the state, but this is no easy task. I am for decentralization, yet this should happen based on discussion with all segments of society. Again, we are in a transitional period, so every decision should be thoroughly thought through.

Al-Masry: What role do you think the council can have in the transitional period, if it’s hard to make decisions at this point in time?

Abdel Hamid: The council’s role is to create awareness, as people can revolt without awareness. This step could be fruitful; when we start a dialogue that raises public awareness, people will know both their rights and duties.

Al-Masry: Publishing is a role that the council takes upon itself, along with other institutions in the ministry like the General Egyptian Book Organization and the General Authority for Cultural Palaces. Is the council considering canceling this function and directing its budget elsewhere?

Abdel Hamid: It cannot be canceled but rather rationalized through coordination with other bodies that play a similar role. That way, the same book would not be published by more than one body.

Al-Masry: But some publishing chains have similar goals, such as presenting new young literary talents in the case of the council’s “First Book” chain and the “Literary Voices” chain published by the General Authority for Cultural Palaces.

Abdel Hamid: I do not have the authority to cancel a committee or chain. This requires a decision from the minister, which the council would then vote on. I was chief of this committee before. All I can promise is that all criticism will be taken into consideration.

Al-Masry Al-Masry: The council’s bursaries are also severely criticized, as there are no clear selection criteria. How would you deal with this criticism?

Abdel Hamid: It should be reconsidered, because some intellectuals are granted huge amounts of money, while others receive very small bursaries. In fact, so many intellectuals are in need, and hence there needs to be clear selection criteria.