The rows of self-harm scars that course upward on the teenager’s forearms from her wrists nearly to her elbows are reminders of dark times.

At age seven, the now 19-year-old was diagnosed with sickle-cell anemia, a hereditary disease that comes with painful symptoms, including inflammation of the hands and feet and frequent infections. She became a regular visitor to a hospital where she was given Tramadol, an opioid medication that brought some relief.

Eventually, though, she began obtaining the medication even when there was no pain.

“When I reached 15, I became addicted to it and wanted to take it no matter how,” she said, her face pale and lips bluish. She described how she would cut her arms with a razor when she was high or depressed. She agreed to discuss her addiction with The Associated Press only on condition of anonymity because of the stigma attached to addiction in Iraq.

She is part of a phenomenon in Iraq’s southern Basra province, where illegal drug use and sales have reached previously unseen levels, mainly among youths, over the last three years. Basra is at the forefront of a nationwide spike in drug sales and consumption that has transformed Iraq from merely a corridor for drug trafficking to neighboring countries.

Since late 2014, arrests for drug dealing and use have nearly doubled in Basra compared to 2011-2014, a senior police officer with the province’s anti-narcotics department said. From October 2015 to December 2017, police arrested 4,035 dealers and users, he said. In 2017 alone the number of arrested late in the year stood at 3,479, the officer said. He spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak to the media.

A Health Ministry official said nationwide the numbers have also nearly doubled in the same three-year period, though specific numbers were not immediately available. He, too, spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak to the media.

Government officials and activists blame Iraq’s porous borders, a widespread ban on alcohol, and corruption and unemployment as reasons for the increase. Though the problem nationwide is low compared to neighboring countries, it is expanding, said Dr. Emad Abdul-Razzaq, the federal Health Ministry’s adviser on psychological wellness. “The reports we have indicate that there is an increase,” he said.

Drug use is most prevalent in Basra, followed by Baghdad and Maysan provinces, authorities say.

Basra borders Iran and Kuwait — two countries where drug use is widespread — and is home to Iraq’s only outlet to the Persian Gulf, from which commercial goods enter the country, making it more vulnerable to trafficking. Large amounts of drugs have been seized in goods containers at Basra ports and border crossings.

The most popular narcotic in Iraq, Abdul-Razzaq said, is crystal methamphetamine, the white crystalline drug produced in neighboring countries and ingested by inhaling, smoking or injecting. Locals simply call it “crystal.” Others turn to drugs prescribed for relieving pain and treating psychological disorders, such as Parkizol, Valium and Somadril as well as morphine-based derivatives like codeine.

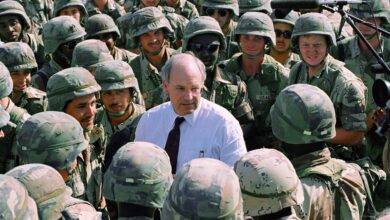

During Saddam Hussein’s rule, sales and possession of narcotics could be punished by a death sentence, which curbed smuggling. However, with the removal of the death sentence after the 2003 U.S.-led invasion that toppled Saddam, Basra saw an increase in the smuggling and sales of narcotics, including new ones like hashish and methamphetamine.

The Basra anti-narcotics officer said that since late 2014, the drug trade has thrived because of a security vacuum left when many forces were moved from the borders to join the fight against the Islamic State group, which swept through nearly a third of Iraq that year. Along with methamphetamine, authorities in the province began to seize hashish and small amounts of opium and pills, he said.

Psychiatrist Aqeel al-Sabbagh said he believes the official statistics on drug abuse don’t reflect the reality in the province.

“When we try to talk to the addicts about others they know, we get the feeling there are whole areas that are completely plagued,” he said.

Al-Sabbagh’s colleague, Nazhat Najim, said crystal meth is the most popular substance in Basra, with 62.1 percent of the country’s consumption located in the province. It’s followed by Tramadol and hashish. The most affected are between the ages of 18 and 30, with 10 to 12 percent of them women, he said.

One meth addict described how he was joking around while high and choked his cousin until he turned blue and lost consciousness. Some women nearby started shouting at him and pushed him off his cousin before he strangled him.

“That was the moment when my family decided to take me to a doctor to heal from drug addiction,” said the 39-year-old, a father of one who works as a gas station attendant, who asked not to be identified. He said he started smoking hashish in cigarettes and then progressed to meth. The AP interviewed him in August when he was receiving treatment.

“At the beginning I had no clue about anything, but step by step and cigarette after a cigarette I found myself joining the crystal club two months later, which completely destroyed me and my family,” he said.

Al-Sabbagh, who supervises the man’s treatment, said that after nearly six months of treatment, he began using again and recently attacked his neighbor and damaged his car. He is now chained in his home and taking medication.

Al-Sabbagh, who heads the psychiatry department at Basra General Hospital, said the country lacks specialized rehabilitation centers and medicine and suffers from a severe shortage of psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers. He advises his patients to seek treatment abroad — mostly Iran, Jordan and Egypt.

Early this year, Iraq is set to open its first specialized mental health and rehabilitation center in Basra with about 40 beds after al-Sabbagh pleaded for years for such a facility. He’s still awaiting authorities’ approval to hire doctors and psychiatrists from Egypt to treat patients and train Iraqis.

Facing a growing problem, Basra’s Anti-Narcotics Department was transformed from a small office with 15 troops and an officer in 2014 to a department boasting 195 troops and 17 officers. Another 85 security members will join soon. Last year, it added two new detention halls to the existing one to cope with increasing numbers of addicts and dealers.

“We still need financial support, sniffer dogs, modern drug detectors and vehicles … and the perfect number for security forces is 750,” said the senior officer who spoke anonymously.

Hoping to raise awareness among youths, 50-year-old activist Sameer al-Maliki is directing a film on addiction. Titled “The Price,” it tells the story of two unemployed friends who are hired by a drug dealer in return for free narcotics. One of them kills the other’s father when he decides to inform the police.

“If the situation continues to worsen … I’m sure we’ll see drug addiction becoming a normal habit in Basra even in public areas,” he warned.