The title of Bensalem Himmich's 2008 novel, "Haza al-Andalusi!" ("This Andalusian!"), is as subdued in Arabic as it is attention-grabbing in English. In translation, it becomes "A Muslim Suicide," a title that sprawls across the book's cover in bright block letters.

But this new title, translator Roger Allen explains, is not a betrayal of the author's intentions. In fact, it hews very closely to the author's original wishes. According to Allen's afterword, Himmich had wanted to call the book "Al-Intihar bi-Jiwar al-Ka'aba" ("Suicide Beside the Ka'aba") for the way his protagonist reportedly died in AD 1269.

Himmich isn't sure that his main character was a suicide. "A Muslim Suicide," like Himmich's celebrated "The Polymath," is a carefully crafted historical novel that takes a philosopher as its hero. "A Muslim Suicide" follows 13th-century Sufi philosopher Ibn Sab'in as he struggles to maintain his independence from authorities. Ibn Sab'in is forced first out of Spain, and then Morocco, and is finally killed — or commits suicide — in Mecca.

"A Muslim Suicide," which was long-listed for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2009, doesn't offer a realistic portrait of Ibn Sab'in's peculiarities, loves and companions. As in previous novels, Himmich diverges sharply from European literary and artistic traditions that value giving the impression of three-dimensional reality.

Certainly, contemporary artists are aware of the limits of "realism," both in the visual arts and in literature. But the European novel tradition nonetheless still creates the expectation that a book will present the "real" and "individual" flaws of its characters. Indeed, beginner novelists are told to make their characters "round," or to give them the appearance of dimensionality.

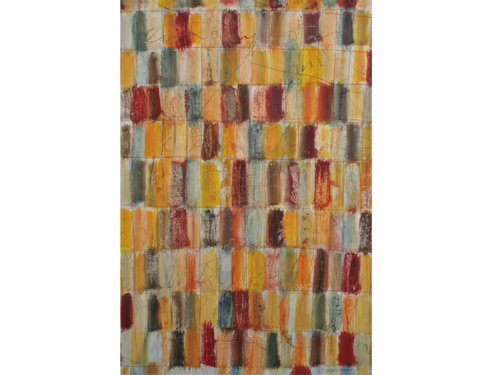

Himmich's novel doesn't do this. We don't learn much about the individual natures of his characters, and none of his characters could be called "round." They are far more like the human figures in Islamic art than the "realistic" images of European portraiture.

The figures in "A Muslim Suicide" are thus not to be enjoyed because we relate to the woes of this 13th-century sage and his companions. It's true that we can see similarities between the rulers and revolutionaries in Himmich's book and rulers and revolutionaries today. But Himmich's book is mostly to be enjoyed for the wonderful florescence of beautiful ideas and details.

Early in the novel, Ibn Sab'in is forced by the ruling authorities to flee Spain. A woman who sits next to him on a boat tells him a sad story about her husband and suckling infant, and Ibn Sab'in gives her money. A fellow passenger tells Ibn Sab'in that this "trickster" woman often rides the boat and tells different stories about her travails. Ibn Sab'in tells him, "You did wrong, my good man!" He goes on to surprise the reader by saying:

"If you'd told me about this beggar woman when she was still with us, I would have given her even more. When this woman is forced to expose herself in public, it's poverty that's showing us the one weapon she possesses, her imagination. That is her only recourse, her means of livelihood, just as is the case with writers who compose poetry, stories, and books of maqamat and zajal poetry."

Much of the pleasure in reading "The Muslim Suicide" is in the contemplative joys of these sorts of moments — as though we, too, were followers of the Sufi sage. There is a plot and a reason to continue turning pages: We must find out what will happen to Ibn Sab'in as he eludes the authorities who attempt to silence him. But, although there is a thrill to Ibn Sab'in's escapes, this is not the book's central pleasure. What make this an enjoyable read are the descriptions of place, period and idea.

At one point, Ibn Sab'in remarks on what makes a "genuine poet." This, he says, is: "Someone who is familiar with the earth and what grows on it and who has learned the vast majority of the terms involved!" This could also be a commentary on the book: Himmich is a writer who is familiar with 13th-century Spain, with what grew on it, and the terms involved.

Allen's translation surely grappled with many complex matters, and his scholarly knowledge of 13th-century Islamic culture is not in doubt. He provides a long glossary at the end to explain more about the "places, battles, texts and authors" who are referenced in Himmich's book. The prose is also clear. But at times, particularly with poetic passages, the language seems to be flattened and somewhat un-joyful.

Nonetheless, there is a happy quietness that comes in reading this book, like going out for a long walk through a beautiful orchard while contemplating both nature's wildness and one's own, constructed soul.