Sleeping on your side rather than your back or stomach might play a role in helping reduce your risk of developing Alzheimer's and other neurological diseases, according to a new study.

Side sleeping opens a passage in the brain called the glymphatic pathway that dispels waste and other chemicals, say the researchers from Stony Brook University in the US.

"It is interesting that the lateral sleep position is already the most popular in human and most animals — even in the wild — and it appears that we have adapted the lateral sleep position to most efficiently clear our brain of the metabolic waste products that built up while we are awake," says Dr. Maiken Nedergaard of the University of Rochester.

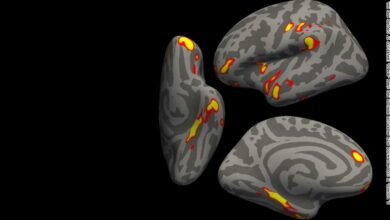

The team's research began years ago when they used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology to observe the glymphatic pathway in rodents.

They learned that the waste-clearing process — bathing the brain with cleansing cerebrospinal fluids (CSF) and interstitial fluid (ISF) — is most efficient during sleep.

What gets flushed out the glymphatic pathway are amyloid β and tau proteins that are unhealthy in the brain if they build up.

In the study, lead author Dr. Helene Benveniste and her team used MRI technology and kinetic modeling to measure the exchange rates of the fluids CSF and ISF in rodents who had been given anesthesia as they slept on their sides, backs and stomachs.

Sure enough, technologies called fluorescence microscopy and radioactive tracing that gave the team a view of the glymphatic pathway revealed increased efficiency when the rodents slept on their sides.

Dr. Nedergaard says the results of the study serve as further proof that sleep serves a waste-eliminating function.

"Many types of dementia are linked to sleep disturbances, including difficulties in falling asleep," she says, suggesting that such disorders may be linked in some way to brain waste not being properly eliminated. "It is increasingly acknowledged that these sleep disturbances may accelerate memory loss in Alzheimer's disease."

Body posture and sleep quality should be assessed in humans as the scientific community begins to lay the groundwork for further research that could enrich our knowledge of these brain diseases, says Dr. Benveniste.

She cautions individuals that the team's research was conducted on rodents and that further experimentation will be needed to determine whether or not their conclusion applies to humans.